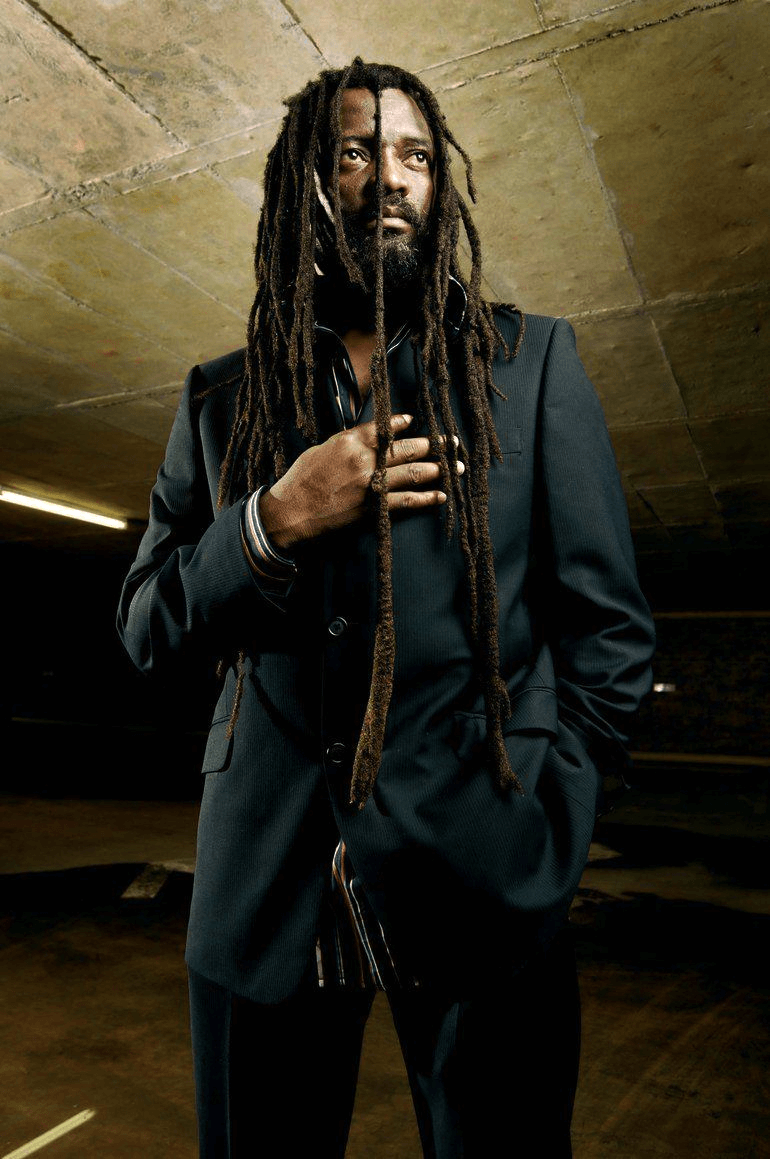

Lucky Dube: South Africa’s Reggae Giant, Rastafarian Humanitarian, International Postcolonial Poet & Philosopher

By: DaQuan Lawrence, PhD Student, African Studies, Howard University

‘…Hey, you government, never try to separate the people

Hey, you politician, never try to separate the people…

They were created in the image of God, and who are you to separate them?

Bible says, He made man in his image, but it didn’t say Black or white.

Look at me, you see BLACK. I look at you, I see WHITE

Now is the time to kick that away and join me in my song.

We’ re different colours, one people. Different colours, one people. Hey, you politician, never separate the people here. Hey, you man hey you man, never try to separate the people

Some were from America. We were from South Africa.

Some were from Japan. We were from China.

Some were from Australia. We were from the U.K.

Some were from Zimbabwe. We were from Ghana.

Some were from Jamaica. We were from Russia”

Lucky Dube

Different Colours, One People, 1993

“Lucky Dube is the only non-Jamaican who continuously [and only] used reggae music and it gave him a space in the heart of the Jamaican people to say, ‘here is an African who is using reggae music and who has gotten over with reggae.’”

Mutabaruka 2012 Interview

Introduction: A Fallen International Icon

The first quote above addresses the significance of racial and ethnic solidarity among humanity despite nationality, geography, and political, social, and economic differentiation. The second quote acknowledges Lucky Dube’s role in the pantheon of artists and musicians as an Africa-born reggae artist. Dube used his music to advocate for unity, human rights, humanitarian aims, and to offer social commentary on social and political issues affecting marginalized populations within the Republic of South Africa (RSA), the African diaspora, as well as the international community. As the 15th year commemoration of Lucky Dube’s impact and legacy approaches, it can be argued that his influence can be compared to the likes of other musical icons who addressed social issues such as Tupac Shakur, Nina Simone, Bob Dylan, Sam Cooke, and Bob Marley.

Born August 3, 1964, Lucky Philip Dube was raised in a small town near Ermelo, which was formerly located in the Eastern Transvaal of the RSA, now of Mpumalanga, and taught in the Afrikaans language. He was a reggae musician, Rastafarian, and South Africa’s biggest selling reggae artist, who recorded 22 albums in Zulu, English and Afrikaans in a 25-year period. Dube was tragically shot and killed at the age of 43, in an attempted vehicle hijacking in Johannesburg on October 18th, 2007.

Lucky Dube is considered especially remarkable as a Dub Artist due to his lack of a diasporic cultural base. This was mainly due to the nature of reggae and Dub being used as a platform for expression of displacement from Africa. On the album, Prisoner (1989), the South African legend adapts the genre by applying themes of apartheid and internal displacement. In the song and music video, Dube is found pushing the bounds of the genre by highlighting the struggles of South Africans. He was revolutionary and presented a competing narrative of reggae’s tendency to romanticize Africa as a utopia.

Dube used Dub as a platform to promote racial equality within Africa during the Apartheid regime. He used his music to frame arguments about the African slave trade, colonialism, and how Africa should benefit those racially identified as Black. In “When Echoes Return: roots, diaspora and possible Africas (a eulogy)”, Louis Chude-Sokei said about Dube:

“What Lucky Dube’s music did was “[present] a praxis of cross-culturality and visionary possibility” that the diaspora at large tends to erase. Dube gave Africa a voice and put its culture on the global stage by joining the global reggae community. Through taking Jamaican roots music back to its roots, he recontextualized the oppression and political struggles that reggae seeps itself in, bringing the basis of the diaspora back in conversation with the diaspora at large to allow for a more pan-African form of cultural expression. Dube’s roots reggae brought African people to the table in terms of conversation about the black diaspora by mimicking Caribbean artists’ assertions of African authenticity or racial utopia.

In his abstract to the article, “Lucky Philip Dube: The Artiste in Search of a New Jurisprudence and Subaltern Redemption”, Eric Nsuh Zuhmboshi said about Dube:

“Most musicians, in their songs, portray their philosophical vision of life as could be seen in the case of Lucky Philip Dube, the black South African reggae musician. His songs show that he adheres to the principle of ethical humanism and portrays him as a crusader of social justice. Thus, this essay shows the link between musical art and law by examining the commitment of Dube’s lyrical composition in fighting for a just legal system in his society. This essay, therefore, analyses some of his lyrical productions in order to expound on the philosophical ideas underneath the songs and how they tie with the search of an alternative jurisprudence and humanism in postcolonial discourse and the liberation of the subaltern. From the perspective of natural law theory, this essay postulates that Dube’s songs criticise the injustice of the legal philosophy in his society and quest for an impartial jurisprudence – that of equality and justice in his society.”

This article considers Dube’s musical career, international impact, cultural significance, and lyrical content, and argues that Dube was an international Rastafarian humanitarian, postcolonial poet, and philosopher. The article seeks to critically assess the social commentary, arguments and calls to action found in Dube’s music, which include themes of anti-apartheid, anti-racialism, anti-war, and anti-discrimination against marginalized groups such as women and children. As we approach the 15th year commemoration of his legacy since Dube’s tragic passing, it is important to recognize the legend’s contributions to society within music and in the realms of philosophy and post-colonial African theory. Dube’s lyrics in the songs, “Slave” (1987), “Together as One” (1988), “Group Areas Act” (1991), “War and Crime” (1989), and “The Way It Is” (1999) are extremely poignant, poetic, and both socially and politically conscious, proving that African epistemological and ontological philosophy can be found in various genres of African and diaspora-based music.

Background: South Africa’s Reggae Giant

Dube’s parents separated before his birth. As a result, he was raised by his mother, who named him Lucky because she considered his birth fortunate after a number of failed pregnancies. Dube and his two siblings, Thandi and Mandla, spent a lot of his childhood with his grandmother, Sarah, while his mother worked. In a 1999 interview, he described his grandmother as “his greatest love” who “multiplied many things to bring up this responsible individual that I am today.”

As a child, Dube worked as a gardener but attended school when he recognized that he wasn’t earning enough to help feed his family. He ultimately joined a choir with his friends, and formed his first musical group called The Skyway Band.. During his matriculation in school he discovered the Rastafari movement.

At age 18, Dube joined his cousin’s band, The Love Brothers, playing Zulu pop music known as mbaqanga. During this time, he also worked as a security guard at the car auctions in Midrand, South Africa. The band signed with Teal Record Company, later incorporated into Gallo Record Company), and though Dube was still in school, recorded in Johannesburg during his school holidays. After their second album was released, in which Dube wrote some of the lyrics in addition to singing, he also began to learn English.

During his fifth album, Dave Segal became Dube’s sound engineer and encouraged him to change his stage name. From this point on, Dube’s albums were recorded as Lucky Dube. He eventually discovered fans liked the reggae songs he played at concerts. Drawing inspiration from Peter Tosh, he felt the socio-political messages related to Jamaican reggae were applicable to an institutionally racist, South African society.

Dube decided to try reggae, and in 1984, released the EP album Rastas Never Die. Although the record sold poorly in comparison to the 30,000 units his mbaqanga records would sell, Dube was motivated by anti-apartheid activism, which led the apartheid regime to ban the album in 1985, because of its critical lyrics. Dube performed the reggae tracks live, wrote and produced a second reggae album, Think About the Children (1985). The sophomore reggae album achieved platinum sales and established Dube as a prevalent reggae artist in South Africa, in addition to attracting international attention.

Dube continued to release commercially successful albums and in 1989, he won four OKTV Awards for Prisoner, won another for Captured Live the following year, and another two for House of Exile in 1991. His 1993 album, Victims, sold over one million copies worldwide and in 1995, Dube earned a worldwide recording contract with Motown Records.

Dube won the “Best Selling African Recording Artist” at the World Music Awards and the “International Artist of the Year” at the Ghana Music Awards in the early and mid-90s. His following three albums won South African Music Awards. During this period, Dube toured internationally, sharing stages with artists such as Sinéad O’Connor, Peter Gabriel, and Sting.

Global Humanitarian, Postcolonial Poet & Philosopher

Between 1984-2004, Dube produced 14 reggae albums during the anti-apartheid period: Rastas Never Dies (1984); Think About the Children (1985); Slave (1987); Together as One (1988); Prisoner (1989); Captured Live (1990); House of Exile (1991); Victims (1993); Trinity (1995); Taxman (1997); The Way It Is (1999); Rastas Never Dies + Think About the Children (2000); Soul Taker (2001); and, The Other Side (2003).

In order to demonstrate that Dube was an international Rastafarian humanitarian, postcolonial poet, and philosopher, this article will examine some of the lyrical content of Dube’s lyrics, utilizing five of his albums as case studies: Slave (1987), Together as One (1988), Prisoner (1989), House Of Exile (1991), and The Way It Is (1999).

The album, Slave (1987), features seven songs: Slave; Let Jah Be Praised; I’ve Got You Babe; Oh My Son [I’m Sorry]; Rasta Man; Back To My Roots; and, The Hand That Giveth. The title track, Slave, includes social commentary about the role of liquor and alcoholism in society, as well as religion, unemployment, and gender-based violence:

[Verse 1]: Ministers of religion have visited me many times to talk about it. They say to me: ‘I gotta leave it. I gotta leave it. It’s a bad habit for a man’. But when I try to leave it my friends keep telling me ‘I’m a fool amongst fools’.

[Chorus]: Now I’m a slave, (a slave). I’m a slave, I’m a liquor slave. I’m a slave, (a slave, slave). I’m a slave. Just a liquor slave.

[Verse 2]: I have lost my dignity I had before trying to please everybody. Some say to me: ‘Yo, yo, I look better when I’m drunk’, some say “no, no, no. I look bad you know. Sometimes I cry. I cry but my crying never helps me none…. [Chorus]…

[Verse 3]: Every night when I’m coming back home, my wife gets worried because she knows she’s got double trouble coming home. Sometimes I cry (I cry) lord I cry, but my crying never helps me.

This song’s lyrics are important because they call attention to the role of alcoholism in South African society, especially among the Black (and Coloured) South African population. Dube’s lyrics also focus on the marginalization African women experience as a byproduct of the dehumanization of African men in Southern Africa. When Black South African men had difficult experiences in society, alcohol use increased the possibility of violence toward Black South African women. Furthermore, the song elucidates the internal conflicts marginalized men experience when trying to overcome their mental, social, and psychological issues.

The album, Together as One (1988), features eight songs: Together as One; Eyes of The Beholder; On My Own; Women; Truth in The World; Children In The Streets; Jah Save Us; and, Rastas. The title track, Together as One, is an explicit call for unity amid the ongoing tension and political oppression various Black South Africans experienced under the Republic of South Africa’s apartheid regime:

[Verse 1] In my whole life, my whole life, I’ve got a dream. In my whole life, my whole life, I’ve got a dream. Too many people hate apartheid, why do you like it? Too many people hate apartheid, why do you like it?

[Chorus]: Hey you Rasta man, hey European, Indian man, we’ve got to come together as one. Hey, you Rasta man, hey European, Indian man, we’ve got to come together as one. Hey, you Rasta man, hey European, Indian man, we’ve got to come together as one, not forgetting the Japanese.

[Verse 2]: The cats and the dogs have forgiven each other, what is wrong with us? The cats and the dogs have forgiven each other, what is wrong with us? All these years fighting each other but no solution. All those years fighting each other, but no solution

[Verse 3] In my whole life, my whole life, I’ve got a dream. In my whole life, my whole life, I’ve got a dream. Too many people hate apartheid, why do you like it? Too many people hate apartheid, why do you like it?”

The lyrics of “Together as One” are very moving, especially considering the media narratives and depictions of apartheid society within the Republic of South Africa as racially tense, with members of all racial groups experiencing social and political backlash. Despite the state-sanctioned violence and persecution of Black South Africans by the RSA, Dube continued to advocate for unity and racial solidarity internationally and within the RSA.

The album, Prisoner (1989), also features eight songs: Prisoner; War and Crime; Don’t Cry; Reggae Song; Dracula; False Prophets; Remember Me; and, Jah Live. On track three, War and Crime, Dube further engages in anti-war and anti-apartheid political commentary, as he makes another explicit call for unity and both anti-racial and anti-ethnic discrimination:

[Verse 1]: “Everywhere in the world people are fighting for freedom. Nobody knows what is right, nobody knows what is wrong. The Black man says it’s the white man, the white man say it’s the black man. Indians say it’s the Coloureds, Coloureds say it’s everyone. Your mother didn’t tell you the truth, because my father didn’t tell me the truth. Nobody knows what is wrong and what is right. How long is this gonna last because we’ve come so far so fast. When it started, you and I were not there so…”

[Chorus]: “Why don’t we bury down apartheid, fight down war and crime, racial discrimination, tribal discrimination”.

[Verse 2]: “You and I were not there when it started, we don’ t know where it’s coming from. And where it’s going so why don’t we? I’m not saying this because I’m a coward, but I’m thinking of the lives that we lose every time we fight. Killing innocent people, women and children (yeah). Who doesn’t know about the governments who doesn’t know about the wars? Your mother didn’t tell you the truth, because my father did not tell me the truth…[Chorus]…”

Dube’s lyrics in War and Crime, explicitly demand that the various racial groups of the Republic of South Africa work together to address apartheid policies and overcome racial and ethnic based discrimination. The historical themes of the lyrics call attention the agency younger generations of South Africans have when addressing social, political, and economic issues of the present and future.

The album, House Of Exile (1991), features eleven songs: House Of Exile; Crazy World; Group Areas Act; Reap What You Sow; It’s Not Easy; Running; Falling; Hold On; Up With Hope [Down With Dope]; Can’t Blame You; and, Mickey Mouse Freedom. Track number three of the album, Group Areas Act, calls attention to the three acts (1951, 1957, and 1966) of the apartheid regime’s Parliament of South Africa, which assigned racial groups to distinct residential and business sections under urban apartheid:

[Chorus]: (If I’m dreaming) don’t wake me up. (If it’s a lie) don’t tell me the truth. ‘Cause what the truth will do, it’s gonna hurt my heart.

[Hook]: Being in the darkness for so long now. Mr. President, did I hear you well last night on TV. You said: ‘Group Areas Act is going, Apartheid is going. Group Areas Act is going, Apartheid is going.’

[Verse 1]: Ina me eye me sight the future so bright. I mean, in my eyes I see the future so bright. When the Black man comin’ together with the whitey man comin’, the whitey man coming together with the Black man. The Black man comin’ together with the whitey man comin’, the whitey man coming together with the Black man.

[Chorus]: (If I’m dreaming) don’t wake me up. (If it’s a lie) don’t tell me the truth.

[Verse 2]: Gazing at my crystal ball, I see the future so bright. The fighting’s gonna stop now, we’ll forgive and forget. I know Mr. President you can’t please everyone, but everybody liked it, when you said:

[Hook]: ‘Group Areas Act is going, Apartheid is going. Group Areas Act is going, Apartheid is going.’ And the Black man comin’ together with the whitey man comin’, the whitey man coming together with the Black man. The Black man comin’ together with the whitey man comin’, the whitey man coming together with the Black man.

[Chorus]: (If I’m dreaming) don’t wake me up. (If it’s a lie) don’t tell me the truth. (If I’m dreaming) don’t wake me up. (If it’s a lie) don’t tell me the truth. (If I’m dreaming) don’t wake me up. (If it’s a lie) don’t tell me the truth.”

In the song, Group Areas Act, Dube continues to compound his lyrics with commentary about political, social, and economic issues within South African society. On the track, Dube theorizes and postulates about the potential of a post-apartheid society to have Black and white people occupy the same spaces, free of any racial tension.

The final album, The Way It Is (1999), features ten songs: Crying Games; Crime & Corruption; The Way It Is; You Stand Alone; Man In The City; Let The Band Play On; Man In The Mirror; Rolling Stone; Til You Lose It All; and, The Show Goes On. On the track “The Way It Is”, Dube highlights the strained and one-way relationship between South African politicians, the nation’s business and middle class, and those who supported liberation movement, with the latter group perpetually receiving inadequate resources in a post-apartheid South African society:

[Verse 1]: Didn’t I raise my voice high enough for you. I was running like a fugitive all the time. Risking rejection from my own people, yeah. Now that you got what you wanted; you don’t even know my name. It’s so funny, we don’t talk anymore. Be good to the people on your way up the ladder, ‘cause you’ll need them on your way down.

[Chorus:] That’ s the way it is (the way it is). That’ s the way it is (the way it is). That’ s the way it is (the way it is). That’ s the way it is (the way it is).

[Verse 2]: Didn’t I raise my fists high enough for you? I guess I can’t pat myself on the shoulder for a job well done. Dodging bullets in the streets, I was there risking rejection from my own people, yeah. Now that you got what you wanted; you don’ t even know my name. Remember, be good to the people on your way up the ladder ‘cause you’ll need them on your way down

[Chorus:] That’ s the way it is (the way it is). That’ s the way it is (the way it is). That’ s the way it is (the way it is). That’ s the way it is (the way it is). That’ s the way it is (the way it is). Be good to the people on your way up the ladder ‘cause you’ll need them on your way down.”

Lucky Dube’s lyrics on “The Way It Is”, critique the behavior of the political and economic affluent classes of South Africans after they periodically engage with South Africans who experience economic, political, and social marginalization. Dube’s lyrics call attention to the fact that after elections and business deals, members of South Africa’s economic elite tend to forget about the needs of working class, underemployed, and unemployed South Africans, who were very active in the liberation movement, and anti-colonial and anti-Apartheid struggles.

The lyrical content analyzed in the aforementioned songs contain themes such as anti-colonialism, anti-apartheid, anti-racialism, anti-war and imperialism, as well as calls to eradicate gender-based violence, alcoholism, xenophobia, and both ethnic and race-based discrimination. Lucky Dube undoubtedly was aware of the humanitarian, human rights, and social justice themes found in his music. In an 1995-6 interview, Lucky Dube stated:

“…while to some people being a Rastafarian is about having dread locked hair, to me it is about consciousness, be it socially or politically…I write my music about people, myself, and real things that are happening to real people. No song that I have written has been about imaginary things. All the songs I have written, people have been able to relate to them in some way…There are three reasons that I do music: to educate, to entertain, and to unite.”

As a result, the position of this author and article is that Lucky Dube should be recognized as an international (Rastafarian) post-colonial philosopher, poet and humanitarian.

Conclusion:

Lucky Dube is unquestionably one of the greatest artists of the late 20th and early 21st century period. Dube was a humanitarian, who strove to unite South African society and the world at-large, using his revolutionary music to advocate for racial and ethnic solidarity, and anti-discrimination against women, children, and marginalized populations. The themes found in Dube’s music are intentional in order to conscientize and politicize his audience about the potential of humanity and human solidarity. As a result, Lucky Dube should be recognized as an international humanitarian, post-colonial poet, and philosopher in addition to being considered as a musical icon and staple within the pantheon of music legends who have contributed to global society.

With 22 recorded albums in Zulu, English and Afrikaans in a 25-year period, Lucky Dube has created more than 120 recorded songs in his career. This case study utilized five songs from five of Dube’s albums recorded across a 12-year period, which spanned across the anti-apartheid movement during the Republic of South Africa’s apartheid regime and the post-apartheid period: Slave (1987), Together as One (1988), Prisoner (1989), House of Exile (1991), and The Way It Is (1999).

The songs, “Slave” (1987), “Together as One” (1988), “Group Areas Act” (1991), War and Crime” (1989), and “The Way It Is” (1999) contain strong, emotional lyrics, that postulate and advance human rights, racial and ethnic solidarity, and the eradication of discrimination and xenophobia. Furthermore, Dube’s lyrics contain poetic, dynamic, and universal calls for social justice and the abolition of the apartheid policies. Dube’s humanitarian philosophy and poetic lyrical ability centralized the African diaspora. Considering potential micro-, or interpersonal, and macro-, or group; and social organization, levels of application, Dube’s songs of social and political consciousness provide a compass for aspirations of a greater humanity.

As 2022 marks the 15th year commemoration of the legacy of Lucky Dube, let the world reflect on his proverbs, actions, and calls for racial and ethnic solidarity, eradication of discrimination against women and children, and a more just and loving society, and seek ways to normalize such values in modern day and our future society.

Bibliography

Car Jacker Kills Reggae Star, 2007. CNN, 19 October

Chude-Sokei, L. 2011. “When Echoes Return: roots, diaspora and possible Africas (a eulogy)”

Condolences Pour in for Lucky Dube. 2007. SABC News

Factbox: Five facts about reggae star Lucky Dube

“Getting Lucky”. 1999. The Mail & Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 September 2007

Grobier, R. 2020. “SA has a serious gender violence problem, and alcohol is the main culprit.” News 24

Interview with Lucky Dube. Youtube. Accessed April 19th, 2022

“Is Alcohol Fueling South Africa’s GBV crisis?”. 2020. Crossroads Recovery Centres.

Lucky Dube Discography. Reggae Discography.com

Lucky Dube. 1993. “Different Colours, One People” Lyrics. Victims. Shanachie Records

Lucky Dube. 1991. “Group Areas Act” Lyrics. House of Exile. Gallo Music Productions.

Lucky Dube. 1987. “Slave” Lyrics. Slave. Gallo Record Company.

Lucky Dube. 1988. “Together as One” Lyrics. Together as One. Gallo Record Company.

Lucky Dube. 1999. “The Way It Is” Lyrics. The Way It Is. Shanachie Records

Lucky Dube. 1989. “War and Crime” Lyrics. Prisoner. Gallo Record Company.

Mabin, A. 1992. Comprehensive Segregation: The Origins of the Group Areas Act and Its Planning Apparatuses.

Mr. Lucky Dube – The Way Back Machine Internet Archive

“Mutabaruka Interview on Lucky Dube”. 2012. YouTube

Zuhmboshi E.N. 2021. “Lucky Philip Dube: The Artiste in Search of a New Jurisprudence and Subaltern Redemption”